Chapter 3

Vision in Concert

When I began writing this essay in May 2014, I knew that I wanted to convey the power of collaboration, sensitivity and mutual respect in getting things done. I had expected to approach these ideas conceptually, but surprised myself when I immediately and effortlessly began illuminating the gifts of the people I was fortunate enough to have around me during the process. I wasn’t sure where I was going with this approach, but I allowed it to flow forward to see where it would lead me.

When I returned to the writing in October, I was able to see with fresh eyes just what I was getting at. Looking over the descriptions, I noticed a pattern of looking for and easily finding what made me want to bring in certain people, and more importantly, how much I wanted to serve their gifts and do what I could to bring them to the fore. Great performances or visual flourishes were achieved in most cases, by getting out of people’s way and letting them shine in the way that they shine naturally.

In this chapter, I want to introduce some of the people that joined me and TJ in contributing to the vision of Eleventh Hour Shine. The next chapter offers more of a narrative behind the process and places that narrative in a larger social context.

The first person I want to introduce is my older sister. As we will see, her presence is deeply felt throughout the whole album, and her narrative factors largely in the final chapter, which is called “The Phantom Heart.”

Wendy

After landing back in Boston and meeting with T. J. about recording an album, I set out to secure the funds to begin working on what was later to be called Eleventh Hour Shine.

On a warm Sunday morning, I drove to Hookset, New Hampshire and asked my sister Wendy to lend me the money to begin the project. To my surprise, she offered to lend me $3000. I was grateful and delighted. Wendy and I grew up singing together, and more than most, she had my back throughout my entire life. But, she was also by nature a dreamer for herself and for others and told me she would do anything she could to help me to fulfill mine. It was a great honor to have her trust me with a personal loan of this size, and I was determined to make good on that loan and to pay back every penny.

In later months, I was able to repay the full amount. It was in September, just a few days after my birthday, a time of the year I’ve always loved -and a time in my life when Eleventh Hour Shine and so much else was coming together for me in my personal, professional and artistic life.

But, then the unimaginable happened.

Late in the evening on October 1st, I received a voicemail from my stepfather, Tom, urging me to call my mother as soon as possible. As I dialed to return the call, I was preparing myself to learn that my Mom had been diagnosed with a fatal disease. Standing outside on the sidewalk after a night of hanging out with friends, I listened as my mother’s neighbor informed me that Wendy had been pulled over by a state trooper and that she had suddenly taken off, leading police on a high speed chase. In the background, I could hear my mother crying and calling my name.

I knew. I just knew.

The woman spoke to me calmly as she said “I don’t know how to say this, Steven…. but…”

I abruptly cut her off and asked “is she dead?”

She paused, then answered, “yes.”

My mother called out to me from the background, but I told the woman that I could not talk to anyone. I hung up the phone.

“Not Wendy. Not Wendy!” I cried out.

We grew up making music together, recording cassette tapes for hours on end, singing along to ELO albums, The Beatles, the Xanadu, Pete’s Dragon and Tom Sawyer soundtracks, and Donnie & Marie records. We had been through a lot together as children, eventually running away from Maine to Massachusetts, seeking a new life far away from the fear, violence and degrading poverty we had known for so long. In my aunt’s words, we were “twin souls”. Though our life paths brought each of us into entirely different networks with a wide chasm between the availability of choice between us, there had always been an intimate sameness that I cannot describe so easily in words. Not long after Wendy’s death, I became friends with her community through social media. One of her close friends told me on the phone that Wendy often told people that I was her “rock in life.”

Knowing that I was Wendy’s rock has made it all the more difficult for me to accept that I couldn’t have prevented this tragedy somehow. All that is left is the self-assigned task of writing about nonviolent speech, ethical leadership and the magnanimous use of power and influence. There is a part of me that hopes that promoting these principles in even a small way might help prevent these kinds of tragedies from occurring in others’ lives. In the final chapter, I will explore this in more detail.

As I am writing this, I am aware that this is the first time I’ve mentioned the tragedy in writing in a publicly available forum. I am no longer reeling in shock from the impact of Wendy’s death, but I am left to wonder what to make of the events that led up to her tragic end and how to integrate that loss into my personal narrative in a way that is healing for me and potentially helpful to others. I have been tempted to leave this tragedy out of the narrative behind Eleventh Hour Shine, but how can storytelling of any kind be honest when the parts that haunt us are not brought to light?

As the city of Ferguson, Missouri burns in righteous anger and large cities across the country explode with protests, looting and riots in response to the police killing of an unarmed young black man, I am pondering the question of whether my silence on Wendy’s homicide continues to be the right action. I am pondering whether my reluctance to take on the cause of “police brutality” is an adequate response. I am pondering whether I will ever come to the decision to throw my hat in the ring and contribute to the conversation about the abuse of power by people in uniform.

Yet, I know that I have something else to contribute. For now, my contribution is an essay on leadership, collaboration and the benevolent use of personal influence and power. It is an appropriate response, because these themes transcend and include the debates around public policy, including educational and social policy, and law enforcement practices.

I began writing this essay eight months after my sister’s death, knowing that I was working on themes much larger than “the making of the album.” I had originally planned to leave Wendy’s death vague to keep the essay’s overarching themes from becoming entangled in sensationalism and cheap emotionality. Yet, when I consider the nature of her death, the media’s reductionistic depictions of who she was, the cruel online commentary, and my understanding of the ways in which institutions that serve the public interest often fail to serve that common good, I have to recognize that Wendy’s life and death is indeed central to the themes of the songs on Eleventh Hour Shine and to the urgency of responding to a word of extraordinary need.

Wendy’s life, legacy and generosity was the single, greatest contribution to Eleventh Hour Shine, and for this and many other reasons, I’ve dedicated the album to her.

And there were others

I wanted to build Eleventh Hour Shine in concert with others, and I was fortunate to find the right people. First and foremost, I wanted to work with people who were collaborative by nature, good people who could work together in a non-competitive environment.

Below are some of the key people.

Adam

The first person I thought of for the recording project was Adam. Adam had already supplied the backing vocals, synthesizer and brass instruments for Marcel long before we decided to include that piece on Eleventh Hour Shine. We had successfully worked together on a variety of music projects over the years, and taught music together in a summer program, where we produced fairly ambitious musical concerts with middle school students. So, asking Adam to work on Eleventh Hour Shine was hardly a choice. It was pre-ordained.

Adam’s working ways are characterized by diligent craftsmanship, easy and open communication, and a parallel appreciation for excellence in others and the ability to find it in himself. A perfect blend of humility and confidence that makes him an effective musical director, a gifted teacher, and a valuable friend. What he brought to the studio project, above all else, is a kind of non conceptual positivity that made all of us feel like “we got this.”

For me personally, Adam’s grasp of the big picture and his skills with multiple instruments has been a welcome relief. On many occasions, I have been able to rely on Adam to pull things together in the manner of a hired musical director, and I’ve observed in myself and others the easy willingness to embrace his stewardship whenever he stepped forward to fill that important role.

To say that Adam “gets” collaboration is a hell of an understatement. He ain’t heavy. He’s our brother.

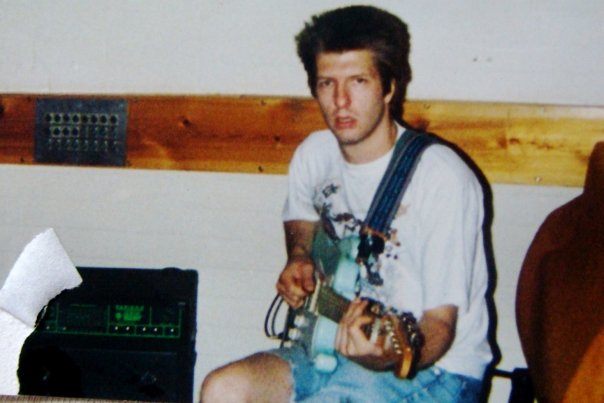

Ernie

Ernie is one of those people, I think, who might appreciate a little less coverage than most, not so much out of excessive modesty but because he just likes to do great work, and likes to keep it at that.

That said, I want to convey the subtlety with which Ernie approaches guitar work and creative relationships, at least in my experience. Without a doubt, he is experimental at heart, meaning he is willing to toss out whatever parameters that may have been established when beginning to lay down a guitar track. At the same time, he seems determined to truly understand a song, including its lyrical meaning and compositional structure in order to serve it best.

In a word, I would describe his mode of artistry and collegiality as “relational.” Whether he is relating to a moment of inspiration, the mood of a room, an unfolding pattern of a song or the organization of a rehearsal schedule, nothing is lost on him, and he responds without hesitation yet in a spontaneous way that helps things come together for the good of all.

Needless to say, this ability to feel out the total situation or music piece is an enormous asset in any group endeavor. Even more, Ernie’s willingness to ask for direction and capacity for trying things out for the sake of playful experimentation added a beautiful variety of sounds to the record.

In the end, the quality I admire the most in Ernie is his empathy and heart. In academic circles and in some performing arts cultures, this may not be the coolest thing to openly admire in someone, but for me, it’s a key ingredient.

Bob

Bob is an uncle. Or maybe he is not. He certainly is avuncular. Unbridled childlike enthusiasm, killer drummer instincts, unperturbably upbeat sense of humor, and a meticulous composer-like attention to detail from the micro to the macro levels of a recording… all of these things make Bob Bob. This is a pun that Bob would have made had he been writing this.

During our recording and mixing process, Bob stepped forward way beyond the “hired hand” mentality of a session musician or even “just the drummer.” When T. J. and I were stuck and needed feedback, we often called Bob in to give us the needed jumpstart to move forward. This was partly due to the collaborative culture we intentionally created, and of course the fact that the right people contributed to the project.

Bob was the right person. I immediately thought to ask him to join this project when I decided I wanted to record “Bucket of Paint” a song he and I used to jam to together back when I first wrote it in 2002. While I originally asked him to play just this one song, he wound up playing on almost all of them, and became in effect a major, major partner in stewarding the music to completion in its final stages.

Bob’s personality is overwhelmingly positive and he is one of the best backup singers and drummers I’ve ever worked with.

Mike

Bob introduced me to Mike when I was looking for a bassist to record on Eleventh Hour Shine. He insisted that Mike was a great bassist, a quick study, and an all-around accomplished musician. Boy, was he right.

What strikes me most about Mike in his studio work and general approach to ideas and projects is the remarkable speed at which he picks up on things and his intense engagement with the material. I would say that his chief characteristic is a love for problem-solving, perhaps a characteristic we both share in equal measure. Whether it’s how to market our project during a crowd-funding campaign, or whether to reduce the volume of a layer of background vocals, he possesses an intense curiosity about it all, satisfied with actively participating in the journey regardless of the outcome.

At first, Mike was literally a “hired hand” and came in to get the job done, but, as the project progressed, we started having longer phone conversations, and when he wasn’t occupied teaching music or being a responsive father, he would stop by to offer feedback, as we refined the album to completion.

To say the least, he is an enjoyable counterpart for exchanging ideas musically, intellectually and philosophically. I call his working style synaptic collegiality, and I feel we’re all the better for it.

Whose Vision?

In the final analysis, given the capacities of key players with these and other qualities, it would be quite an undertaking to determine the source and genesis of a project’s vision. But, it’s worth the effort when we consider the important issues of power, authority, money, freedom, agency, innovation and how organizations function and change.

The visual elements for Eleventh Hour Shine came about in the same way. The website and CD designs, music videos and branding were the result of electrified dialogue, collaborative craftsmanship, discomforting critique, exponential learning, and wide-eyed inspiration.

There were moments when a design or visual element turned out so perfectly that I could have sworn I did it all myself. Not in the sense that I wanted to get the credit, but in the sense that a draft or final result felt so utterly familiar and “just right” that it felt like it had the genetic code of Truth in it.

In this realm, I had much more to learn, and I had four teachers.

Chris

My longtime friend and film partner, Chris introduced me to analog and digital formats for shooting and editing film and video. Although I had studied filmmaking at the Boston Film & Video Foundation in the 1990s, it was Chris who turned me onto the joys of shooting 16mm color negative film, and various types of Super 8 film cartridges. What’s more, Chris taught me how to use Final Cut Pro, which transformed my artistic life in a major way. The editing skills I’ve developed with this incredible software have enabled me to create entire visions, including music videos, short films, and experimental fictional documentaries (Eric Left Riverton).

- For Eleventh Hour Shine, Chris shot interior scenes of me and Adam for the long form video/short film Marcel/Don’t Be Afraid. He also lent me his Super 8 camera when I journeyed across the country to the Mohave Desert to shoot scenes for the video. To date, not a single artist has had more of an influence on my learning in the cinematic arts.

Tracey

Another major influence for me in the visual arts is the work of filmmaker, Tracey. She shot a number of scenes in Eric Left Riverton, and taught me how to compose shots and to experiment with camera movement. Her unique style made its way into my own and directly affected the choices I made behind the camera in Eric Left Riverton, the promo videos for Eleventh Hour Shine, and the video for Marcel/Don’t Be Afraid.

Jesse

Aside from playing the acoustic guitar for the song “Coolyani”, Jesse shot and directed the final scene and creative pickup shots for Marcel’s Opus. After seeing the rough edit for “Marcel’s Opus”, in which a rock concert dream sequence takes place, Jesse insisted that my original concept be dispensed with in favor of what turned out to be a much better approach. I had originally shot and planned to edit in a metaphorical audience for the sequence, having filmed hundreds of construction barrels with blinking orange lights as a stand-in for a rock concert audience.

Jesse broached the subject of changing the vision with a straightforward critique, respectful, tactful and to the point. “Don’t release the video, as is, Steve” he exhorted, almost like a warning. Then he explained why staging a rock concert would be more effective than suggesting a rock concert metaphorically, no matter how “experimental” it may appear.

He was persistent. Standing outside James Gate, a restaurant/pub in Jamaica Plain, Jesse refused to allow for my protestations about creativity, metaphor and the perfect synchronicity of chancing upon a large crowd of orange lane markers at a truck stop in Arizona. As far as Jesse saw it, not shooting a rock concert sequence would be a wasted opportunity.

I was persuaded. I agreed to walk the dog of the person who would lend him the equipment. He agreed to shoot the scene with every professional resource he had at his disposal.

Using top-notch, professional lighting, digital cinema cameras, and other quality gear, we rocked out on a Sunday night at a performance space in Jamaica Plain. Adam, T. J. and I were the only musicians onstage, and used broken, shoddy instruments, some of which are not even in the song. Adam, for example, is playing a keytar onstage, which isn’t featured in the recording. Due to a scheduling conflict, we were not able to secure a whole drum-set, just a few parts, and we even had to lay the snare on top of a bucket and move forward without cymbals.

This added to the dream element and compelled us to shoot the scene not so much for realism but for emotional impact.

Jesse hung high-end backlighting to silhouette the band, using tight shots, and fast camera movements to suggest a massive audience. We only had five people in the audience, but it looks like we have hundreds, thanks to Jesse’s work. We did four takes, and I lip-synced to the song, and did every rock star move I have ever been exposed to, and allowed myself to let go and play the part. The fact that the song was played over the sound system at a high volume really helped me to get into the character. This, too, was Jesse’s idea.

But, Jesse played a significant role in achieving this vision far beyond offering his technical expertise and resources. As we will see, his contribution to seeing this project to its end was mighty indeed.

Alex

One evening in the fall of 2012, I was having a pint of Guinness at a favorite spot in Jamaica Plain, when I met Alex, a gifted 30-year-old with a wide variety of skills in the digital arts including photography, web design, digital cinema (filming and editing), musical instruments, poetry and non-fiction.

I didn’t know these things about Alex until I returned to Boston in April, 2013 after my cross-country trip to shoot Marcel’s Opus.

Like the proverbial onion, getting to know Alex over the following months into the summer was getting to know an unimaginable array of conceptual, philosophical and creative layers that not only fascinated me but gradually came to influence my approach to the vision of Eleventh Hour Shine and beyond.

Alex designed the CD cover for Eleventh Hour Shine and the websites for Pragnus Gray Collective and Eric Left Riverton. We worked alongside each other for many weeks to build the visual designs. For reasons I still don’t understand, Alex took hold of my vision and made it his personal mission to make it happen. Beyond the products he and I created other, this young man’s influence and encouragement ultimately transformed the entire canvas of my work in many arenas. I’ll have more to say about this in the final chapter, which I would like to dedicate to him. The title of this chapter is “The Phantom Heart”, a metaphor Alex came up with to describe my experience a few days after Wendy’s death.

In the final chapter, I allow myself to get a little personal. After all, what use are all these theories and frameworks if they are not meaningfully connected to our little lives on the ground level? And, in the absence of the meaningful integration of some the more positive leadership attributes I have described, what kind of outcomes can we expect?

I must be simple and frank here. We can expect devastation.